Defending yourself against cross-site scripting attacks with Content-Security-Policy

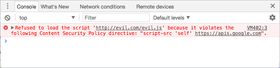

I spent an entire day last week wrestling with a PDF-rendering library in React which was refusing to work in production. Locally it ran just fine, but as soon as we built our app in production mode, it wasn't doing anything. Looking at the console, the errors it was spitting out made my heart sink. I'd seen these before.

This was an error caused by our Content-Security-Policy (CSP) header, telling our browser that something in the library should be blocked - specifically, an eval() function within one of the dependencies of our PDF-rendering library. I did what any self-respecting developer would do and complained at anyone who would listen - okay, I posted on Twitter - and then discovered that a lot of other developers weren't aware of what CSP was or what it was for. So I thought I'd write a post about it.

The error messages I was getting were protecting me against a common web security vulnerability - cross-site scripting attacks (XSS). As a web developer, it's really important to be aware of what XSS is and how to prevent it.

Contents

- Cross-site scripting (XSS)

- Content-Security-Policy is a set of rules about permitted content on a website

- How to create a CSP header

- Adding to a CSP header

- The moral of the story

- References & further reading

Cross-site scripting (XSS)

XSS involves someone injecting malicious code into an unsuspecting website, which then executes on the victim's computer.

This injected code can do things like:

- copy your cookies and send them to the attacker

- get information about your location or data from your webcam etc

- grab session tokens from local storage

On websites that store sensitive information, such as banking or shopping websites, XSS vulnerabilities could allow someone to impersonate you by stealing your access token and using it to log in as you - which means gold-plated toilet seats for them, and a nice credit card bill for you.

The Open Web Application Security Project (OWASP) recognises three different methods of XSS: stored, reflected and DOM-based.

Stored XSS

Stored XSS refers to malicious code sent in the server response from something like a database.

Example: on a website allowing people to submit comments to discuss news articles, a user submits the following comment:

Great stuff guys!<script>/* sneaky code */</script>

If the website isn't sanitizing any user input (stripping it of any HTML tags) and is rendering the comment directly into the DOM, that script will execute as soon as you load the page it's on. Before you know it, your browser has posted comments all over the site declaring your support for some deeply unpleasant organisation.

There's a really interesting episode of the podcast Darknet Diaries featuring Samy, the (accidental) creator of a MySpace worm that used XSS to get people's profiles to automatically add him as a friend. This is a great example of stored XSS, because it all started with something he posted on his own profile (which was then stored in MySpace's database).

Reflected XSS

This is where malicious user input in a request is sent back in the immediate server response, executing on the receiving client's browser.

Example: someone posts a link online to a shopping website, with a search term in the URL so it takes you directly to the catalog page. But they've also included some <script> tags in the query string.

https://niche-tshirts.com/shirts?q=extreme+ironing<script>/* sneaky code */</script>

When the server receives the request, it takes the entire query string and uses that as the search parameter. In the HTML that it returns, it renders:

<p>You searched for: amateur paleontology<script>/* sneaky code */</script></p>Then, your poor unsuspecting browser will execute what's between those script tags, and the attacker will be able to gain access to your access token and anything else they've managed to scrape.

DOM-based XSS

Finally, DOM-based XSS is when JavaScript running on the page uses data from somewhere the attacker can control, such as window.location (the URL of the page). Say we have some JS on our page which takes window.location and then executes some function with it:

https://niche-tshirts.com/shirts?q=spelunking

const params = new URLSearchParams(document.location.search.substring(1))

const searchTerm = params.get("q")

document.getElementById("content").innerHTML = `<p>You searched for: ${searchTerm}</p>`If our attacker from before sends another link with the <script> tags in the query string, these will be rendered into the DOM when the browser sets the inner HTML content of the #content element.

Unlike the previous two examples, this all happens client-side - the server isn't involved at all.

Preventing XSS

Some of the methods we can use to prevent XSS attacks on our websites include:

- sanitizing user input, making sure there are no HTML tags in it

- escape certain characters (like

<,>,&, and") with HTML entity encoding (e.g.&for &) to prevent them being executed - not rendering arbitrary content from the server as HTML - render it as plain text

- check the Content-Type is correct - only

text/htmlif you are definitely returning HTML - use HttpOnly cookies for sensitive data so that the JavaScript

Document.cookieAPI can't access them - and... set up a

Content-Security-Policyheader!

Content-Security-Policy is a set of rules about permitted content on a website

Content-Security-Policy is an additional layer of security on a site, preventing things like malicious scripts from being run by defining strict rules about what content you can and can't have on a website. It can be one of the HTTP headers that we can send from the web server to the client (browser), or a meta tag in the <head> of an HTML page. A browser will read the CSP and check whether the scripts, stylesheets and various other resources it's executing or displaying conform to the rules in the policy. If not, it won't load them.

A CSP meta tag may look a bit like this, for a site with Google Analytics and some Twitter/Facebook embeds, and images from a CDN:

<meta http-equiv="Content-Security-Policy" content="default-src 'none'; manifest-src 'none'; prefetch-src 'none'; worker-src 'none'; object-src 'self'; font-src *; connect-src 'self' https://www.google-analytics.com; img-src 'self' https://some-cdn.com; script-src 'self' https://platform.twitter.com https://www.google-analytics.com https://connect.facebook.net https://staticxx.facebook.com; style-src 'self' https://platform.twitter.com">

The CSP header or meta tag content is always a string containing a semicolon-separated list of rules.

A policy has a list of directives which are usually suffixed with -src, and refer to different kinds of rules for resources and content on the page.

Some common categories of directive are:

- fetch directives: which resource types may be loaded, and where from

- document directives: what properties the document or worker may have

- navigation directives: where a user on the page can navigate to/submit a form to

Next to each directive we specify one or more permitted sources for each of these directives.

script-src: 'self' https://othersite.com;

<!-- directive: source source; -->I won't go through every single directive - there are a lot - but I'll outline some of the most common ones, and what rules they might enforce. Plus, the good old caveat that Internet Explorer only supports one directive (sandbox), and that's with the legacy X-Content-Security-Policy header.

While the HTTP header and meta tags are mostly the same, the main differences are that HTTP headers have wider browser support, support all of the directives (meta tags support most of the directives) and may be cached by proxies (meta tags won't be).

As long as you're employing multiple methods of defence against XSS, including CSP, you can protect yourself (yes, even in IE). It's important to emphasise here that CSP is one way of protecting your website against XSS - it's not enough on its own.

Fetch directives

These directives govern which resource types may be loaded, and where from. Things like images, scripts, styles and frames will be defined here.

Any of these directives may also have a wildcard value (*), which basically means "anything goes".

image-src: Permitted sources for any images/favicons on the page.

script-src: Permitted sources for any JavaScript on the page.

style-src: What kind of CSS it's allowed to load, and where from.

font-src: where fonts specified by the CSS @font-face rule may be fetched from (e.g. Google Fonts)

frame-src: where iframes may load content from (e.g. Stripe elements)

connect-src: hosts that your JavaScript may make requests to (e.g. an API, with fetch)

default-src: the fallback if any of the rules don't match the resource

Document directives

Document directives restrict the use of plugins (such as with <embed>) and let us enable sandbox mode.

plugin-types: allows you to define permitted MIME types for embedded media and elements using <embed> tags. These days, you rarely need to use embed, so I don't expect you'll come across this one very much.

sandbox: literally the only directive that IE supports! This allows you to restrict the browser environment on the page, effectively blocking everything - popups, scripts, forms, you name it. It has different sources from the rest of the directives - you can specify exactly what should be enabled in sandbox mode. Take a look at the MDN documentation on sandbox for more information.

Navigation directives

form-action: if you're using traditional HTML forms with action attributes, this directive specifies the URIs you're allowed to submit to.

frame-ancestors: specifies which pages or URIs are allowed to embed iframes and other frame/embeddable content.

Sources

Most directives have the same possible list of sources. With the exception of host source and scheme source, they are all specified in single quotes.

'self'- anything from the same host is fine. So a CSP for localghost.dev withimage-src: 'self'andscript-src: 'self'would be allowed to display images and run scripts from localghost.dev.- a host source : external hosts that the resource can come from.

- For example,

style-src: "https://myhost.com"allows you to include a stylesheet from myhost.com, e.g.<link rel="stylesheet" href="https://myhost.com/style.css"/>. - If you often use content delivery networks (CDNs), you'll need to specify them here. You can also use wildcards for the subdomain of the URL, and restrict things to specific ports as well. The protocol matters, so a host source with

https://will not allow anything fromhttp://. - e.g.

connect-src: 'self' https://*.localghost.devwill allow anything over HTTPS from a subdomain of this site.

- For example,

- a scheme source: what scheme (protocol) it's okay to fetch resources from. Chiefly

https:orhttp:. 'unsafe-inline': whether inline<style>/<script>tags are allowed. I've only really used this forscript-srcandstyle-srcbefore. I'll talk more about why inline style and script tags are a security risk later in the article.'unsafe-eval': whether or not JS is allowed to use theeval()function, which executes arbitrary code from whatever string is passed in. I'll go into more detail about why this is a bad thing in a later section.nonce- you may specify an unguessable cryptographic nonce (a base-64 encoded string) which you can then pass into inline styles or scripts as an attribute to allow them to load on the page. This means you can use inline<style nonce="mysecretstring">or<script>tags without indiscriminately allowing all inline styles - effectively marking only a specific set of inline styles as "safe". This must be randomly generated and unguessable, otherwise it's basically pointless as anyone can guess the hash and pop it in their injected scripts.- hashes - e.g.

sha256-<your hash value>. This is a base64-encoded representation of your inline styles or scripts, so the browser can check the hash against its own hash of the<style>/<script>to make sure it's the real deal. Anything that doesn't match the hash will be ignored. Hashes are static, while nonces are generated server-side on every page load. none- no URLs match, no nothing may be loaded at all. For example, I don't use iframes on this site at all, so I'd haveframe-src: none.

unsafe-inline and the risks of inline styles

But why would we have to explicitly enable unsafe-inline for style-src, and why are inline <style> tags considered "unsafe"?

There are actually a few vulnerabilities that can be triggered using CSS. They're rare and, yes, less harmful than JS-based XSS attacks, but it's still worth protecting yourself against them.

- messing up your site's styles - on a big-name website or app, this can cause reputational damage

- injecting styles into the page to add unsolicited content or offensive text

- disguising user-generated content to look like official content, e.g. a fake login link

All of these can be prevented with unsafe-inline, meaning the browser will only pay attention to the styles from your defined stylesheets.

Ultimately, allowing unsafe-inline is a calculated risk: if you really can't get around it with a nonce or a hash, then you can enable this knowing that you are introducing a slight vulnerability, but it's highly unlikely to be anything super severe.

There's a helpful StackOverflow answer which explains this in more detail.

Scripts, unsafe-inline and unsafe-eval: why eval() is evil

While enabling unsafe-inline for styles is not the end of the world, it's a bad idea to allow it for scripts. A lot of harm can be done with an inline script that's been injected into your code - with a connect-src directive defined as well it would mean that that script couldn't connect to any other sources, but it could still cause havoc, such as pretending to be you and updating user-generated content.

eval(), on the other hand, should be avoided at all costs. It takes a string as a parameter, and blindly executes it as Javascript. There's literally a section in the MDN article about eval() called "Never use eval()!". This opens up a whole host of security vulnerabilities - if unsafe-eval is enabled, anyone can execute arbitrary code in your application. Yikes.

How to create a CSP header

In a static site, you can add a meta tag to your site's <head>:

<meta http-equiv="Content-Security-Policy" content="default-src 'none'; manifest-src 'none'; prefetch-src 'none'; worker-src 'none'; object-src 'self'; font-src *; connect-src 'self' https://www.google-analytics.com; img-src 'self' https://some-cdn.com; script-src 'self' 'sha256-flsjfljlkfjaspdjfsdkgs' https://platform.twitter.com https://www.google-analytics.com https://connect.facebook.net https://staticxx.facebook.com; style-src 'self' 'nonce-adsfasdfasfsadf' https://platform.twitter.com">If you're running an app with an Express server, you can easily set it as one of the response headers with helmet-csp - check out the Helmet docs for more information.

The safest method is to have the most restrictive CSP possible, and only add new sources if you're completely sure. Include a default-src: 'none' so that if no rule matches a resource, it will be blocked.

Adding to a CSP header

When is it safe to add new sources to a CSP header? Perhaps you've included an image or stylesheet in your code, and your browser is refusing to render it because it violates the CSP. Before adding the URL as a source, consider:

- do you trust this site?

- how specific can you make the URI? (avoid wildcards unless it's a host you control)

- could you host the file on an already approved source?

- could you add the CSS file to your repo instead?

styled-components and unsafe-inline

If you're using styled-components, which renders <style> tags into the page, rather than enabling unsafe-inline for styles you can define a nonce by setting it as a Webpack global (__webpack_nonce__). The caveats: this is apparently undocumented, and only works with server-side rendered code. So you might have to enable unsafe-inline for that one.

Environment-based CSP

If you run different environments for development and production, you may want to consider serving different CSP headers for different environments. For example, your image-src directive might point to a non-prod CDN if process.env.NODE_ENV !== 'production, but the production CDN otherwise. Similarly, if you use a local server at localhost:6060 as an API for development but your production app points to a hosted API somewhere else, you might want to add localhost:6060 to your CSP only for the development environment.

There are some frameworks, such as Hugo and Next.JS, which rely on inline scripts for hot reloading. In this case, it's fine to add unsafe-inline to your script-src in development.

For example, if you use Hugo and want to enable live reloading with your CSP, as well as scripts imported from the site itself, you can use .Site.IsServer (though this only works if you use server mode for development and not production):

<meta http-equiv="Content-Security-Policy"

content="default-src 'none'; [...] script-src 'self' {{ if eq .Site.IsServer true }}'unsafe-inline'{{ end}} {{ .Site.BaseURL }};">The moral of the story

So, how did I get around the unsafe-eval warnings I was seeing in the console?

Unfortunately... the only solution was to chuck out that library and find something else. There are no workarounds for a library that uses eval.

When adding a CSP header to a site, start out with the principle of least privilege: only permit exactly what you need, nothing more. When in doubt, be overly restrictive, and see what console errors you're getting.

If you're working on a site or app that has a CSP header set, don't be tempted to add sources just to make console errors go away. Make sure you know exactly what you're allowing.

And promise me you will never, ever enable unsafe-eval.

References & further reading

Cloudflare - What is Cross-Site Scripting?

Google's CSP Evaluator can check how watertight your CSP is (but is not exhaustive).